Inside ‘The Gallerist’ Score: Joseph Shirley and Andrew Orkin on Turning Art Basel Chaos Into Music

Courtesy of Sundance

The composers break down co-scoring Cathy Yan’s Sundance satire, building a wall-to-wall soundscape that moves like the camera and balances high jinks with real emotional weight.

Some Sundance films arrive with the kind of logline that feels engineered to start a bidding war. Others arrive with something more dangerous: a premise so absurd it can only work if every department commits to the bit with total precision. Cathy Yan’s ‘The Gallerist’ belongs in the second category — a film that dares you to believe it exists, then doubles down on the audacity. The story’s hook is already legendary in Park City circles: a gallerist conspires to sell a dead body as conceptual art during Art Basel Miami. It’s the kind of pitch that sounds like satire written by someone who’s been trapped at a VIP afterparty for too long, overhearing collectors explain “meaning” while treating art like a stock portfolio.

But what makes a film like this actually land isn’t just the concept. It’s tone. Tone is the difference between a sharp, stylish thriller-comedy and something that collapses under its own cleverness. And tone is where music becomes the secret weapon. That’s why the film’s score has been one of the most intriguing pieces of the ‘The Gallerist’ conversation heading into Sundance — not just because it’s wall-to-wall, but because it has to behave like a shape-shifter: comedy one second, dread the next, then suddenly elegant, romantic, and strangely human. It has to move like the camera, flirt with the absurdity, and still keep the movie feeling expensive, tense, and alive.

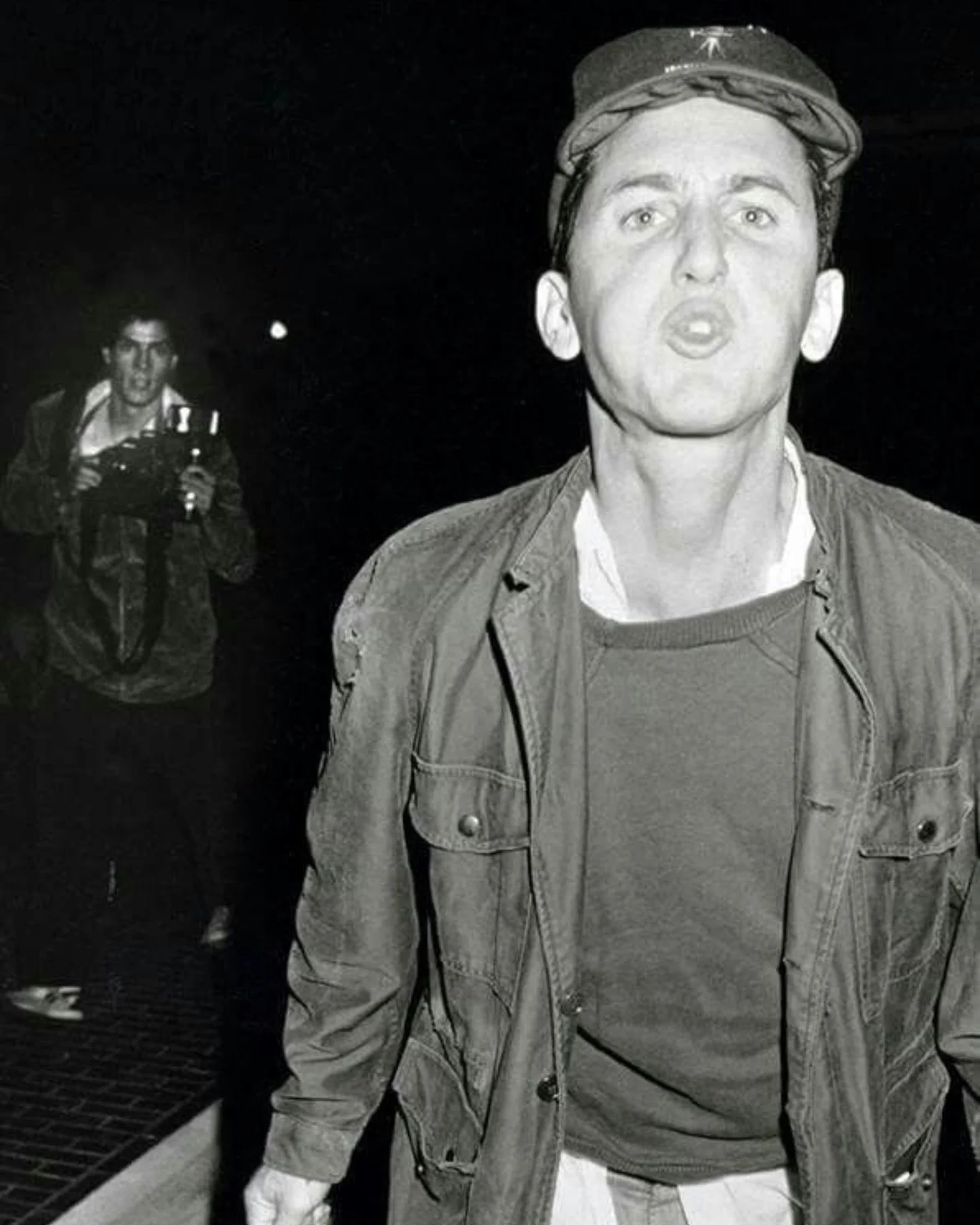

Ahead of the film’s Sundance premiere, I spoke with composers Andrew Orkin and Joseph Shirley about how they built that sound — a co-scoring collaboration that feels less like “two separate voices” and more like one continuous nervous system. Orkin comes into ‘The Gallerist’ with a long history alongside Yan, dating back to their earliest days in New York. Shirley joins as a fresh creative partner, bringing a different musical palette and a new set of instincts, but the two immediately clicked, finding a shared language for the film’s chaos. Orkin described the collaboration as something that’s been years in the making with Yan. “I’ve worked with Cathy for years actually — since we were… she was in film school and I was in music school in New York,” he told me. That creative history includes shorts, pilots, and even work connected to ‘Birds of Prey,’ where Orkin contributed remixes.

Cathy Yan and Andrew Orkin at the 2018 Sundance film festival.

That kind of timeline matters, because ‘The Gallerist’ isn’t the type of film where music is an accessory. It’s part of the structure. Orkin said Yan gave him an early draft of the script back in 2024, and from the start, the conversations weren’t about whether music would matter, but how much. “She gave me the script to read while it was still a work in progress in 2024,” Orkin said. “We… chatted about how important music was for this film. So it’s kind of a driving force, with it being wall-to-wall score.” A wall-to-wall score can be a flex, but it’s also a risk. If you overscore, you suffocate the film. If you underplay it, the energy drops. And because Orkin describes the film as unfolding in a linear timeline — a real-time escalation of bad decisions and spiraling consequences — the score has to act like a propulsion system. “The movie kind of takes place in a linear timeline,” he explained, “so the music kind of needs to transport us in that way.”

That “transport” is where the film’s satire becomes something more complicated than a punchline. Scoring satire is notoriously hard because you’re always deciding whether the music is laughing with the characters, laughing at them, or warning the audience that what they’re watching is darker than it looks. Orkin put it bluntly: “The dark comedy world is always a tricky one. As a composer, you’re treading a very fine line.” And ‘The Gallerist’ isn’t just dark comedy. It’s tonal whiplash by design — a genre-bender that has to serve different characters, camera styles, and emotional beats without feeling like it’s switching playlists mid-scene. Orkin described it as “melding a lot of genres in the score to try and touch on… the different themes, the different camera moves, [and] the different characters.” That “camera moves” detail is crucial, because it hints at something most audiences don’t consciously think about: the score doesn’t just follow the story, it follows the lens. It follows movement. It follows momentum.

Shirley, who worked with Yan for the first time on this film, emphasized how specific and intentional her musical direction was — not in a restrictive way, but in a way that gave the score a clear job to do. “With Cathy, she was so clever with what she wanted the music to do as far as energy and storytelling,” he said. That’s the kind of sentence that tells you this wasn’t a passive process where a composer delivers cues and hopes the director likes them. It was active collaboration. Yan wasn’t just approving music — she was shaping how the score would function as narrative voice. Shirley also pointed out that clarity from a director can be a gift. “Sometimes you work with people who don’t exactly know, which can be liberating for a composer sometimes too,” he said. “But with Cathy, she was so astute and very specific about what she wants the music to say and to do in a scene.” In a film built around a morally deranged premise — selling a corpse as art — specificity is the only way to avoid tonal chaos. Shirley described one of the biggest challenges as learning when to let the audience breathe, figuring out “the balance of when to give the audience room to laugh, or to say, ‘We really want to encourage laughs here,’ and how can we do that musically.”

One of the most fascinating parts of our conversation was hearing them describe what this film “sounds like” before you even see it. The logline is wild enough on its own, but sonically, they weren’t interested in just making it quirky for the sake of quirky. They wanted a palette that felt specific to the setting and the art world’s absurd performance of “taste.” Orkin described the earliest demos as leaning into a twisted, esoteric vibe. “Starting off, I wrote the demo back in 2024 — October of ’24,” he said. “We were kind of leaning into this really esoteric, quirky, kind of bendy and twisted world.” Then comes the Miami layer — a place that isn’t just a location, but an energy. Orkin said there are “nods to Miami,” including “a lot of Latin percussion,” along with “techno elements to kind of bring across the art world.” That combination makes perfect sense: Latin percussion as heat, movement, nightlife; techno as slickness, modernity, the feeling of money moving through rooms.

via Cathy Yan’s Instagram

But then Shirley entered the process and added something that changes the entire texture of the film. Orkin described Shirley bringing “more classical, elegant, elevated string work and piano work” — a layer that he framed as art-world “classiness” that’s “thinly veiled.” That’s the joke, right there. Because the art world sells “classiness” as identity. It sells taste as morality. It sells elitism as truth. And the score can weaponize that contradiction: sound refined, while everything on screen is falling apart. As the film evolved, Orkin said, the score became “a real moving target.” What began as a darker comedy emphasis expanded into something with more dimension. “We realized there were more layers to it,” he said — including “drive to the action sequences” and “some emotional depth.”

Shirley said the score ultimately lands on something cohesive even with all its colors. “I feel like this score has a very signature sound, even with all of the different colors and shades that it includes,” he told me. He described it as “quite a zany sound,” and said it leans into “the comedy, into the darkness, into the chaos of the story,” but also emphasized that the sound has edge. “There’s a bit of an edge to everything — every cue,” he said. Even when it’s supporting something funny, “there’s still a bit of noise — noisy bits included.” That line is the best kind of composer quote because it instantly gives you an image: this isn’t clean, polite comedy scoring. It’s comedy with grit under the fingernails. Shirley also explained that the music is designed to move with the camera like it’s a character: “There’s a lot of camera movements in this movie,” he said. “A lot of the cues sort of carry on with the camera. You’re almost like viewing… the camera is almost like the first audience member. We’re along for the ride with it.”

POPULAR ON THE CINEMA GROUP

When I asked how co-scoring actually works in practice, both composers were quick to kill the myth of it being a neat split down the middle. There wasn’t a clean division like “you do this, I do that.” It was more like building a shared pool of material and constantly reassembling it until the film’s rhythm clicked. Orkin explained they weren’t on set — the film shot in Paris while they were both based in LA — and they were working against a process that kept evolving as edits changed. From the first edit, Orkin said, the film was “a lot longer than the final film.” But because the story is linear, “the narrative and ordering of things doesn’t really change… it’s one thing happening after the next. It happens in real time.” That linear structure shaped the music process: “The score was constructed in a basic sense and then whittled down and changed and maneuvered around the action.”

Via Joe Shirley’s Instagram

As collaborators, Orkin described a mix of dividing and conquering while also layering over each other’s work. “It was stuff I’d written, and a lot of stuff that was what Joe wrote, and some stuff that Joe was writing on top of stuff that I wrote,” he said. And that’s where the score’s cohesion comes from. It’s not two separate voices stitched together — it’s material constantly traded, reshaped, and recontextualized. Orkin explained that Shirley’s contributions weren’t just additions, but transformations. “Often it was string parts that I wrote that Joe then mangled and turned into something else,” he said. “Or some percussion parts of Joe’s that then came into elements of mine.” That’s the kind of collaboration that only works if ego isn’t the priority. Shirley credited their past experiences working with other composers for making them both open to that kind of fluid process. “One of the reasons why Andrew and I work really well together is our experience and past experiences working with other composers already,” Shirley said. “You kind of get a sense of collaboration, and helpfulness, and being open to anything — and being up for anything.”

Orkin described how remote the process really was. “It’s pretty remote and pretty solitary,” he said. Even though the score feels unified, the day-to-day work happens in separate studios, often in isolation. The unity comes from the shared “pot of material” they both pull from. And because the film has so much music, there was constant reshuffling: “Let’s bring in this element from cue 5 and put it in cue 25 and see how that works.” The score was still evolving right up until the end. Orkin said they had “two or three versions of some cues floating around until the very end” — even up to the final mix.

One of the most intriguing teases they offered was about a major song moment in the film — a recognizable needle drop that becomes a kind of gravitational center for the score. Orkin didn’t want to spoil it, but he described it as “a song that everyone knows,” and said it influenced how they built the musical through-line leading up to it. “There’s some really strong song moments in the movie,” he said. “One in particular that I think people will be very excited and enthusiastic to hear… it informed the score.” Shirley expanded on how that idea ties into the film’s playful ruse energy. He described the film’s tone as “high jinks,” “playful,” “mischievous,” and noted that “anytime our characters buy into that ruse, there’s a bit of techno drive.” That techno drive isn’t just style — it’s storytelling. It’s the sound of the scam working. It’s the rhythm of momentum. It’s the musical equivalent of a character deciding, in real time, to commit to the worst possible idea.

As we wrapped, both composers spoke about Sundance as the perfect environment for a film like this — especially because comedy, and particularly dark comedy, often struggles to get the same prestige attention as heavier awards fare. Orkin described the film as something that “runs the gamut of emotions.” “It’s a really good time,” he said. “There’s a big array of high jinks. In some ways it’s a romp. In some ways it’s very deep and thoughtful and emotionally honest.” And then he landed on the core hope: that audiences walk out feeling like they actually had fun. “Having the audience walk away being like, ‘Damn, I just had a lot of fun,’” he said, is part of the mission. In 2026, that’s not a small thing. A film can be entertaining and still be smart. It can be chaotic and still be precise. And it can be a satire without being empty.

Shirley echoed that idea, emphasizing the communal experience. “It’s definitely one of those movies that plays best when seen in a big room with a big crowd,” he said. “Because there’s a lot of laughs, and there’s a lot of gasps, and there’s a lot of surprises.” And maybe that’s the most Sundance thing about it: a film built on a ridiculous premise, elevated by craft, landing as something you want to experience with strangers in a theater.

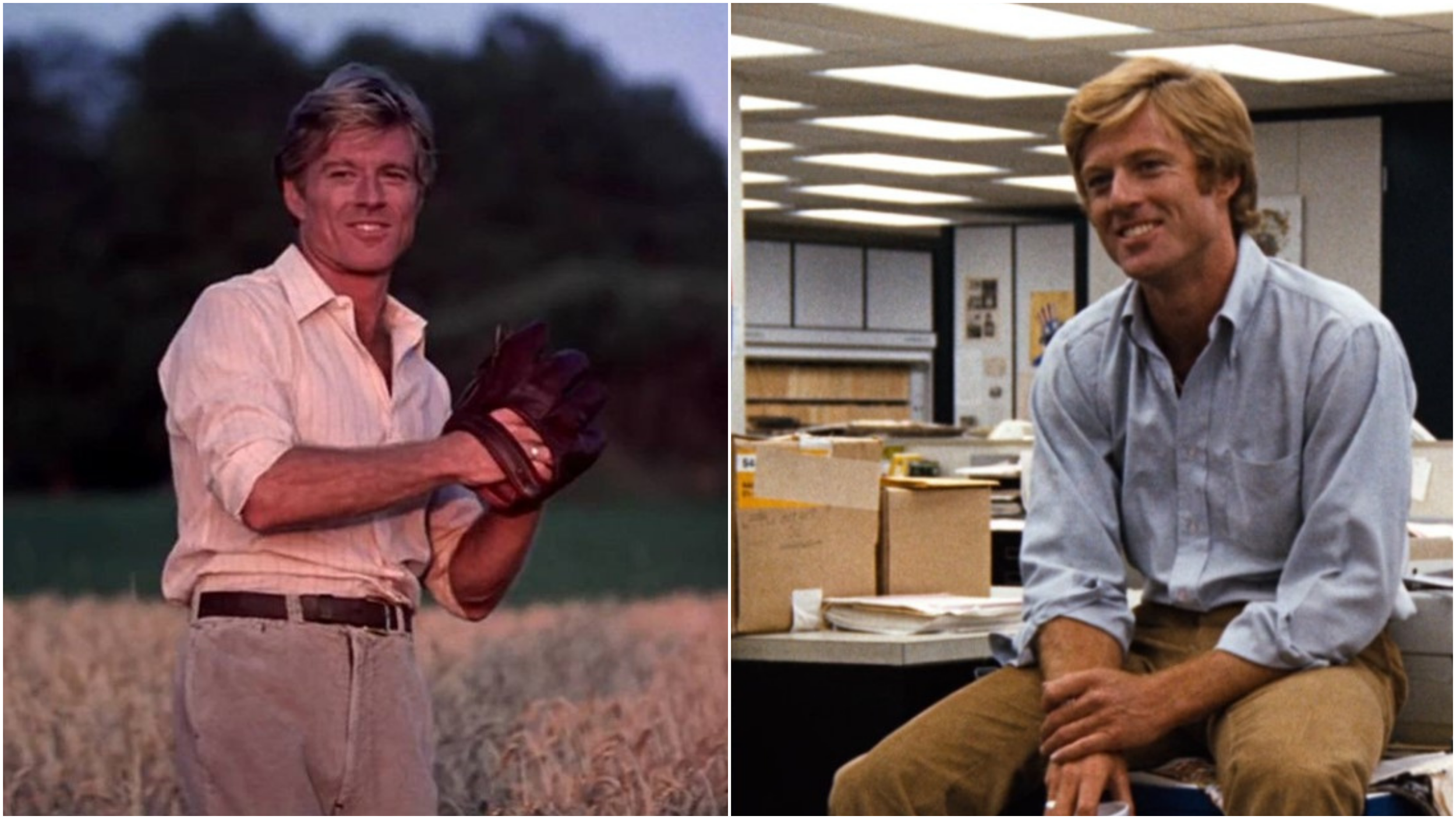

Before we signed off, I asked one last question — a curveball tied to Sundance’s spirit and legacy: was there a score from a Robert Redford film that stood out to them? Orkin brought up ‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’ for its iconic songs, while Shirley landed on ‘All the President’s Men,’ praising the tension and calling it “a killer movie” with “a great score.” Then Orkin came back with another pick he didn’t want to forget: “It’s ‘The Natural’… Randy Newman’s score is literally one of the greatest of all time.” It was the perfect note to end on: two composers talking about film music with the kind of reverence that reminds you why scores matter in the first place — not as background, but as identity.

Robert Redford “in the natural” and “all the presidents men”

And if ‘The Gallerist’ is going to be one of Sundance’s most talked-about premieres, it won’t just be because of the premise. It’ll be because the film’s sound understands exactly what the story is: high art, low behavior, and the thin line between the two.

Courtesy of Sundance

‘The Gallerist’ premieres at the 2026 Sundance Film Festival, and if Orkin and Shirley’s score is any indication, it’s going to be the kind of crowd movie that plays loud, sharp, and unforgettable in a packed Park City theater.