From Justin Bieber to Sydney Sweeney, Celebrities Suddenly Want You to Buy Their Underwear

SYRN

Underwear has become the most intimate — and lucrative — celebrity business yet, and Justin Bieber and Sydney Sweeney are leading the charge.

Underwear used to be private. Quiet. Functional. Something you bought in bulk, never thought about again, and certainly didn’t associate with a celebrity’s personal brand. It lived beneath everything else — unseen, unbranded, unbothered.

That era is officially over.

For years, celebrity branding followed a familiar formula. A famous face, a liquor label, a vague lifestyle pitch, and a launch party engineered to feel spontaneous but unmistakably sponsored. Tequila ruled the 2010s. Then came beauty. Then skincare. Then wellness. And now, quietly but unmistakably, underwear has taken over.

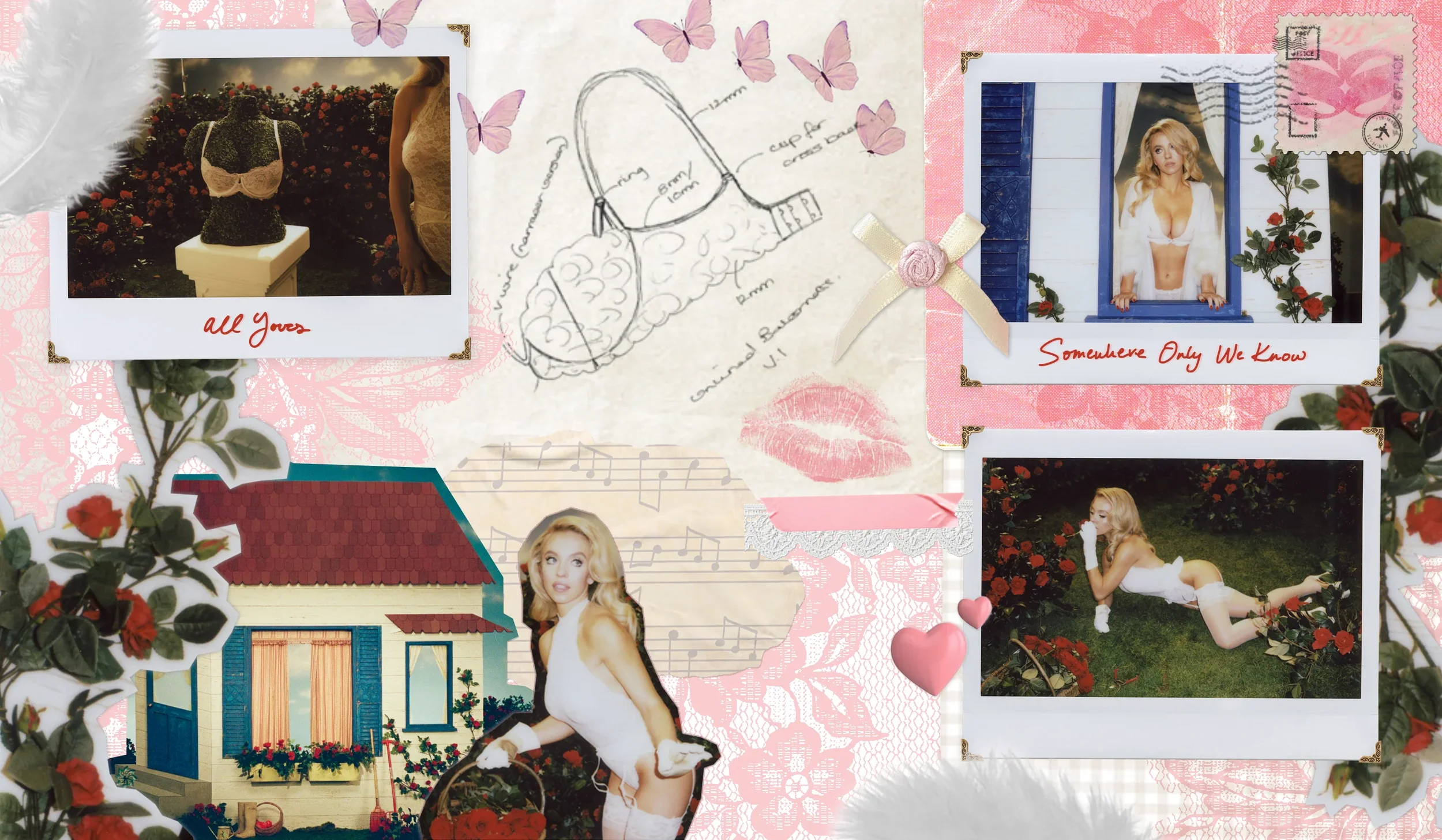

This shift didn’t arrive with fireworks or investor decks leaked to the trades. It arrived with Sydney Sweeney hanging bras from the Hollywood sign, Justin Bieber stepping back into public view wearing nothing but boxers and intention, and a growing sense that the smartest celebrities in Hollywood have stopped licensing their likeness and started monetizing something far more valuable: proximity.

Underwear isn’t just a product category. It’s a relationship. It’s the one garment nobody sees unless invited. And that’s precisely why it works.

In an era where audiences are exhausted by forced relatability and overexposed influencers, underwear offers something different: controlled intimacy, repeat purchases, and margins that don’t depend on trends or trends cycles. It is emotional commerce disguised as fabric. And right now, it’s the most telling signal of where celebrity business is actually heading.

At the center of the moment is Sydney Sweeney — not because she’s the first, but because she might be the most strategic.

Why Underwear Is the Ultimate Celebrity Product

SYRN

Unlike sneakers, fragrance, or hoodies, underwear occupies psychological real estate. It touches skin. It absorbs insecurity, confidence, fantasy, and vulnerability. It’s the first thing you put on and the last thing you take off. It exists in the most private moments of daily life.

So when a celebrity asks you to buy their underwear, they aren’t just selling fabric. They’re collapsing the distance between icon and audience. You don’t become George Clooney by drinking his tequila, but you can feel closer to Justin Bieber by wearing what he wears when no one’s watching.

Underwear isn’t aspirational in the traditional sense. It’s confessional.

Sydney Sweeney and the Business of Being Looked At

Sydney Sweeney knows exactly what she’s doing.

That sentence alone explains about 90 percent of why her new lingerie brand, SYRN, instantly detonated across the internet — and why it matters far beyond bras, underwear, or whatever carefully styled photos you’re about to scroll past. Sweeney isn’t just launching a celebrity side hustle. She’s making a calculated, highly visible move at the intersection of sex appeal, ownership, internet virality, and modern celebrity economics. And she’s doing it at a moment when attention is the most valuable currency in Hollywood — and control over that attention is even more valuable.

Within hours of SYRN’s reveal, the discourse was already familiar: praise, backlash, think pieces, TikToks, feminist hot takes, and screenshots circulating faster than the products themselves. Some called it empowering. Others rolled their eyes. A few accused her of leaning too hard into the male gaze. None of that slowed the momentum. If anything, it fueled it. Because controversy, when handled correctly, doesn’t dilute a brand — it sharpens it. And Sydney Sweeney has quietly become one of the most strategically media-literate celebrities of her generation.

This isn’t accidental. It’s not naive. And it’s definitely not just about underwear.

Sweeney has spent the last several years occupying a very specific, very lucrative cultural position: hyper-visible, hyper-sexualized, critically respected, and constantly underestimated. She is at once the prestige TV actress (Euphoria, The White Lotus), the rom-com lead, the tabloid fixation, and the internet’s favorite object lesson in how Hollywood still consumes women’s bodies. Instead of fighting that reality head-on — or pretending it doesn’t exist — SYRN reframes it as an asset. Not something to escape, but something to monetize, control, and redirect.

Underwear is not a random choice. It is the most intimate product a celebrity can sell without crossing into outright novelty or parody. It lives closest to the body. It trades on desire, fantasy, confidence, vulnerability, and projection. And in 2026, it also trades on parasocial intimacy — the feeling that buying something gets you closer to the person selling it. When Sydney Sweeney sells lingerie, she isn’t just selling fabric. She’s selling proximity to a version of herself the internet already feels entitled to.

That’s the quiet genius of SYRN.

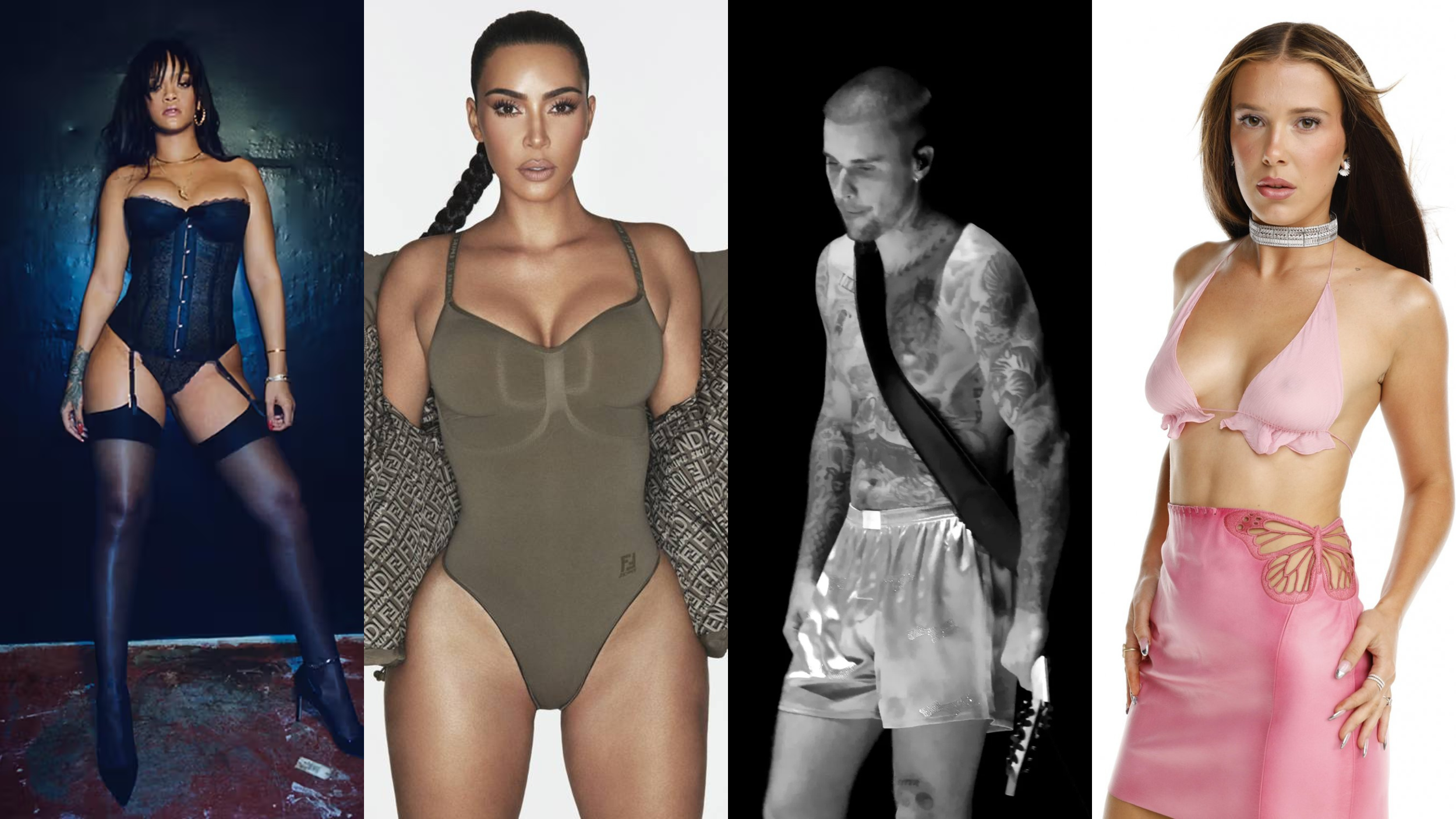

The brand arrives at a moment when celebrity entrepreneurship has matured past tequila bottles and skincare lines and entered a more psychologically sophisticated phase. This is no longer about slapping a famous face on a product and hoping it sells. It’s about aligning the product with the reason the celebrity is famous in the first place. For George Clooney, that was effortless cool. For Rihanna, it was boundary-pushing beauty and inclusivity. For Kim Kardashian, it was control over body image narratives. For Sydney Sweeney, it’s the tension between being constantly looked at — and deciding how, when, and why.

And the clicks prove the point. Sydney Sweeney moves traffic. She dominates search. She drives engagement across demographics that don’t always overlap: young men, young women, fashion audiences, film fans, culture war commentators, and brand analysts all converge around her name. She’s not just famous — she’s algorithmically potent. In a media ecosystem increasingly driven by SEO, social virality, and visual culture, that makes her one of the most commercially valuable celebrities working today.

SYRN, then, isn’t just a lingerie launch. It’s a thesis statement. It asks whether the thing the internet obsesses over — a celebrity’s body — can be turned into a business model that benefits the person being scrutinized instead of everyone else. It challenges the idea that selling sex appeal is inherently unserious or regressive, while quietly acknowledging that pretending sex appeal doesn’t matter has never protected anyone in Hollywood anyway.

This is why SYRN matters more than a hundred other celebrity brand announcements. It’s not trying to disguise itself as altruism or pretend it isn’t provocative. It leans into the gaze — then charges admission.

And Sydney Sweeney isn’t alone.

What makes SYRN feel like a moment, rather than a one-off stunt, is that it sits within a broader shift in celebrity commerce. Justin Bieber selling boxers. Kim Kardashian redefining shapewear as cultural armor. Rihanna building an empire on intimacy and inclusivity. Kylie Jenner monetizing desirability at scale. Millie Bobby Brown leveraging youth, control, and relatability into ownership before most stars her age even understand backend points. These aren’t random pivots — they’re signals. The celebrity endorsement economy is evolving, and underwear may be the most honest expression of where it’s headed.

Because if tequila was about lifestyle aspiration, underwear is about identity.

And right now, Sydney Sweeney owns that conversation.

SYRN Isn’t an Accident: What Sydney Sweeney Is Actually Selling

SYRN

At a glance, SYRN looks like exactly what you’d expect a modern celebrity lingerie launch to look like: moody visuals, clean branding, a name that feels engineered for TikTok captions and search results, and product photography that knows precisely which angles the internet will linger on. But reducing SYRN to “another celebrity underwear line” misses the point — and misunderstands why this one immediately cut through the noise.

Sydney Sweeney didn’t stumble into this lane. She built toward it.

For years, Sweeney has existed in a feedback loop between Hollywood prestige and online fixation. She’s been praised for her performances while simultaneously becoming one of the most dissected bodies on the internet — often without her consent, and often framed as a liability rather than leverage. Interviews, red carpets, comment sections, Reddit threads, and meme culture have all treated her physical appearance as both spectacle and subtext. SYRN doesn’t reject that reality. It accepts it, reframes it, and profits from it.

What SYRN is selling, at its core, is permission.

Permission to feel confident without apologizing for it.

Permission to feel sexy without irony or justification.

Permission to exist in softness, desire, and visibility without having to intellectualize it first.

That messaging isn’t accidental marketing fluff — it’s a direct response to the cultural contradictions Sweeney has been forced to navigate. The brand language mirrors the exact conversations that have followed her career: empowerment versus exploitation, ownership versus objectification, visibility versus agency. By naming those tensions and packaging them into a consumer product, SYRN turns discourse into demand.

And demand, in this case, is measurable.

Celebrity fashion launches live and die by immediacy. If a brand doesn’t generate traction within the first 24 to 72 hours, it quietly fades into the long tail of influencer merch and forgotten Shopify links. SYRN did the opposite. It spiked search interest immediately, dominated entertainment news cycles, and spread across platforms that don’t typically overlap — from fashion TikTok to film Twitter to finance and branding commentary. That kind of cross-audience penetration doesn’t happen unless the product aligns with an existing cultural narrative people are already primed to argue about.

SYRN’s branding also understands a crucial truth about modern commerce: aspiration has changed. Traditional lingerie marketing sold an idealized fantasy — a body type, a lifestyle, a look to aspire toward. SYRN sells recognition. It doesn’t promise transformation. It promises alignment with how people already see Sydney Sweeney: confident, sexual, complicated, and hyper-aware of the gaze directed at her. Buying into the brand isn’t about becoming her — it’s about participating in the story surrounding her.

That’s why SYRN doesn’t need to over-explain itself.

The brand name alone does a lot of work. “SYRN,” pronounced like “siren,” pulls directly from mythological and cultural shorthand — seduction, danger, allure, attention. Sirens don’t ask to be noticed. They are noticed. The name signals intent without spelling it out, which is exactly how modern luxury and semi-luxury brands operate. You’re not supposed to be told why it works. You’re supposed to feel it does.

From a business standpoint, underwear is also a strategic entry point. Compared to outerwear or footwear, lingerie allows for tighter product lines, faster iteration, lower shipping complexity, and higher margins — especially when demand is driven by celebrity association rather than technical innovation. Fit matters, yes, but not in the same way it does for denim or tailoring. Emotional resonance matters more. That makes it an ideal category for a star whose value is rooted in visibility and emotional projection.

SYRN also benefits from timing. The post-pandemic consumer is more willing to spend on items that feel personal, indulgent, and identity-driven rather than purely functional. Lingerie sits squarely in that zone. It’s not about necessity. It’s about mood, self-perception, and ritual. In a moment where people curate their lives online and offline simultaneously, what you wear under your clothes can matter just as much as what you post.

And crucially, SYRN arrives at a moment when celebrity audiences expect ownership, not endorsements. Consumers have grown increasingly skeptical of stars slapping their names on products they clearly don’t control. SYRN’s positioning — from interviews to rollout — emphasizes Sweeney’s involvement, vision, and authorship. Whether or not she’s involved in every operational detail is beside the point. The perception of authorship is what builds trust, and SYRN leans hard into that perception.

This is the difference between a vanity project and a brand with legs.

SYRN doesn’t pretend to be universal. It doesn’t try to please everyone. It knows its audience, understands the discourse around its founder, and leverages both without flinching. That confidence — strategic, not naive — is why it landed the way it did. And it’s why SYRN feels less like a gamble and more like a calculated evolution of Sydney Sweeney’s public persona into something she owns outright.

In other words: SYRN isn’t selling underwear.

It’s selling control over the narrative — stitched, sized, and priced accordingly.

The Internet, the Gaze, and Why the Backlash Is the Business Model

If SYRN felt like it detonated overnight, that’s because it landed directly inside a cultural fault line that has been widening for years: the unresolved tension between empowerment and objectification in the age of social media. Sydney Sweeney didn’t accidentally step into that debate — she built the brand to sit right in the middle of it.

The immediate backlash was predictable. Comment sections filled with familiar refrains: Is this feminist? Is this regressive? Is this just marketing sex? The irony, of course, is that these are the same arguments that have followed Sweeney since her breakout years. SYRN didn’t create the discourse — it monetized it.

The modern celebrity economy runs on attention, but not all attention is equal. Neutral attention is forgettable. Praise is fleeting. Criticism, however, is sticky. It keeps a brand circulating, debated, screenshot, reposted, and algorithmically rewarded. SYRN understands that outrage and fascination often travel together, especially when the product is intimate and the founder is already hyper-visible.

What critics often miss is that the male gaze is no longer something brands simply avoid or embrace — it’s something they repackage. SYRN doesn’t deny that people will sexualize Sweeney or the product. It assumes they will. The difference is that the brand frames that gaze as something acknowledged rather than denied, which disarms a certain kind of criticism while inflaming another. Either way, the brand stays central to the conversation.

This strategy mirrors a broader shift in celebrity branding: stars no longer pretend to be above the internet’s fixation on their bodies. They incorporate it. Kim Kardashian perfected this model years ago by building Skims into a billion-dollar company without ever pretending it wasn’t shaped by how her body was discussed, consumed, and commodified. SYRN operates in that same lineage — just with Gen Z language and post-#MeToo awareness baked in.

The discomfort some people feel about SYRN is, in many ways, the point. Brands that feel “safe” don’t trend. Brands that invite argument do. SYRN isn’t asking to be universally liked; it’s asking to be unavoidable. And in a digital economy driven by engagement metrics rather than moral consensus, that’s the smarter bet.

There’s also a generational shift at play. Younger audiences are less interested in whether a product aligns perfectly with an ideological framework and more interested in whether it feels honest. SYRN’s honesty lies in its refusal to sanitize desire or pretend that sexuality can be neatly categorized as empowering or exploitative. It lives in the gray area — where most real consumer behavior actually exists.

From a business perspective, backlash doesn’t dilute SYRN’s value proposition; it clarifies it. People who are uncomfortable were never the core customer. People who are intrigued, curious, or conflicted — those are the ones clicking through, searching the brand, and, ultimately, buying.

SYRN succeeds because it understands that cultural discomfort is not a liability anymore. It’s a growth engine.

From Tequila to Makeup to Thongs: Why Intimacy Is the Final Celebrity Frontier

SKIMS, CASAMIGOS, KYLIE COSMETICS, 818, SAVAGE X FENTY, RHODDE

Celebrity entrepreneurship didn’t start with underwear. It just ended up there.

The last fifteen years of celebrity branding have followed a clear, almost linear escalation: alcohol, beauty, wellness, fashion — and now intimacy. George Clooney made tequila respectable. Kylie Jenner industrialized beauty virality. Rihanna turned inclusivity into a billion-dollar infrastructure play. Kim Kardashian reframed shapewear as cultural utility. Sydney Sweeney is simply the latest to recognize where the market was always heading.

Tequila worked because it was aspirational but distant. You didn’t have to be George Clooney — you just had to drink what he drank. Beauty pulled the consumer closer. Makeup promised transformation, access, intimacy-by-proxy. Kylie Cosmetics wasn’t just lip kits; it was scarcity economics, influencer fluency, and algorithmic dominance before the industry even had language for it.

From there, the category fractured upward. Victoria Beckham Beauty positioned itself as luxury credibility — clean, minimal, fashion-adjacent, and intentionally restrained. Reese Witherspoon’s Honest brand went the opposite direction, weaponizing trust, motherhood, and transparency into a consumer juggernaut. Hailey Bieber’s Rhode distilled skincare into something even simpler: vibe-first minimalism, clean packaging, and relentless SEO-native marketing that understood exactly how Gen Z shops.

Even Brad Pitt — once the last person you’d expect to sell moisturizer — entered the space with Le Domaine, a prestige skincare line framed around longevity, sustainability, and European winemaking science. The message was clear: beauty isn’t frivolous anymore. It’s identity management. It’s credibility. It’s commerce.

SERGE CHAPUIS

Underwear, however, removes the final layer of distance.

This is where SYRN enters the conversation — and why it feels inevitable rather than opportunistic. Underwear isn’t consumed publicly. It’s not displayed on a shelf at a party or applied in a mirror for Instagram. It’s worn closest to the body. It’s loaded with identity, sexuality, comfort, insecurity, and desire. Unlike tequila or lipstick, underwear is private. Which makes the purchase feel personal, even when it’s mass-produced.

Sydney Sweeney understands this instinctively. SYRN isn’t selling bras and panties as commodities; it’s selling permission. Permission to feel sexy without irony. Permission to want attention without apology. Permission to be confident without having to intellectualize it. That framing lands precisely because consumers are exhausted by brands that over-explain themselves.

John Shearer/Getty Images

Justin Bieber’s Skylrk plays the same intimacy game from a different angle. His boxers, socks, and loungewear lean into softness, comfort, and emotional vulnerability rather than seduction. It’s intimacy without exhibitionism. SYRN, by contrast, leans into allure — not as shock value, but as self-possession. Both strategies work because they recognize the same truth: clothing closest to the body creates the strongest emotional attachment.

From a business standpoint, underwear is a near-perfect category. High margins. High repeat purchase behavior. Size differentiation that encourages multiple buys. Drop culture that sustains momentum. Unlike alcohol, there’s no regulatory burden. Unlike entertainment, there’s no box office risk. Once fit and trust are established, loyalty follows quickly.

That’s why so many celebrities have quietly migrated here. Savage X Fenty didn’t just normalize size diversity — it normalized underwear as identity. Skims didn’t just sell shapewear — it redefined utility as sexy. SYRN enters a crowded space, but it does so with a distinct advantage: Sweeney’s brand is already built on visibility, virality, and desire.

This is the difference between older celebrity brands and the new generation. SYRN doesn’t feel like a side hustle because it isn’t one. It’s vertically aligned with Sweeney’s career, her image, and the way she already circulates online. It’s built for clicks, conversions, and conversation — not just shelves.

In many ways, underwear is the logical endpoint of celebrity branding because it collapses the gap between public image and private desire. You’re not just buying a product endorsed by a celebrity — you’re buying into how they frame intimacy, confidence, and self-worth.

And once you’ve sold someone something they wear under their clothes, you’ve earned a level of brand intimacy that tequila never could.

If the Internet Is Already Sexualizing You, Why Wouldn’t You Monetize It?

SAVAGE X FENTY, SKIMS, Kevin Winter/Getty Images, AB+DM/Glamour

There’s an uncomfortable truth sitting at the center of modern celebrity culture—one that rarely gets said out loud, but is clearly shaping the smartest career moves in Hollywood: if your image is already being sexualized, dissected, memed, monetized, and sold back to the public, why wouldn’t you at least control the transaction?

This isn’t about vanity. It’s about leverage.

Sweeney isn’t inventing this logic. She’s inheriting it—and refining it for a digital economy where visibility is unavoidable and attention is currency. SYRN doesn’t exist because Sweeney suddenly woke up wanting to sell lingerie. It exists because the market already decided she was part of the underwear conversation. The only remaining question was whether she’d be a passive subject or an active owner.

Hollywood history tells us exactly how this playbook works.

Rihanna understood this earlier than most. Long before Savage X Fenty became a multibillion-dollar business, her body, style, and sexuality were already central to how pop culture consumed her. Instead of pushing back against that gaze—or pretending it didn’t exist—she reframed it. Savage X Fenty didn’t just sell lingerie; it sold authorship. Rihanna wasn’t being styled anymore. She was setting the terms. Inclusivity, spectacle, and confidence weren’t just brand values—they were tools of control. The result wasn’t controversy; it was domination.

Kim Kardashian took that framework and industrialized it. Skims didn’t appear out of thin air. It emerged from years of paparazzi fixation, tabloid obsession, and cultural scrutiny of her body. Instead of resisting the microscope, Kardashian turned it into infrastructure. If the world was already obsessed with her silhouette, Skims transformed that obsession into something useful—comfortable, accessible, endlessly scalable. Shapewear stopped being about hiding and started being about ownership. The valuation followed.

The formula isn’t gendered, either.

Justin Bieber’s recent fashion moves—through Skylrk and his ongoing soft-reset aesthetic—operate on the same math, just filtered through a different emotional register. The baggy boxers, the lounge-first silhouettes, the intentionally unpolished vibe aren’t about traditional sex appeal. They’re about proximity. Bieber isn’t selling fantasy; he’s selling intimacy. Vulnerability, softness, and access. And in an era where audiences crave authenticity more than perfection, that intimacy converts.

© @milliebobbybrown

Then there’s Millie Bobby Brown, who quietly executed one of the smartest preemptive moves of the last decade. With Florence by Mills, she built a beauty brand before the industry could fully dictate how her transition from child star to adult actress would be framed. That wasn’t naïveté—it was foresight. Rather than allowing tabloids to narrate that evolution through speculation and sexualization, she established a lane rooted in youth, control, and ownership. It wasn’t reactionary. It was defensive—and brilliant.

Which brings us back to Sydney Sweeney.

Sweeney exists in a media ecosystem that is relentlessly visual, relentlessly thirsty, and relentlessly optimized for clicks. Her image circulates constantly—often stripped of context, nuance, or even relevance to her work. Screenshots outperform performances. Thumbnails outperform scripts. SYRN doesn’t pretend this dynamic doesn’t exist. It simply redirects it. If desire is already being projected onto her, SYRN gives that desire a place to land—cleanly, profitably, and on her terms.

SYRN

This isn’t cynicism. It’s strategy.

Underwear, lingerie, and beauty aren’t accidental categories for celebrities whose likeness already drives engagement. They’re the most honest extension of how modern fame actually operates. These products live at the intersection of identity, aspiration, and intimacy. They don’t require elaborate storytelling to justify. They don’t ask consumers to suspend disbelief. They simply acknowledge what’s already happening.

The smartest celebrities today aren’t asking, “How do I avoid being objectified?” That question assumes control they no longer have. They’re asking something far more pragmatic: If this attention exists regardless, how do I convert it into something I own?

That’s the shift.

SYRN isn’t about selling underwear. It’s about reclaiming agency in an economy that profits off visibility whether the subject participates or not. In that sense, Sydney Sweeney isn’t chasing a trend—she’s closing a loop that celebrity culture opened years ago and pretending never existed.

You can’t stop people from looking.

But you can decide where the money goes.

What This Moment Actually Says About Hollywood, Power, and the Business of Being Seen

SYRN

What this moment actually says about Hollywood, power, and the business of being seen is simple: celebrity is no longer a résumé. It’s a distribution channel. And in 2026, the smartest people in entertainment are treating that channel like an asset they can own, scale, and protect.

Underwear is where the strategy becomes impossible to ignore because it collapses the last remaining distance between brand and audience. Tequila sold lifestyle. Beauty sold transformation. Underwear sells proximity. Not the illusion of being someone else, but the feeling of being closer to someone you already watch, follow, and argue about online. That’s why it converts. It’s private, repeatable, and emotionally loaded. It doesn’t need narrative. The audience brings the narrative with them.

SYRN works because Sydney Sweeney understands something the industry still pretends is impolite to say: her visibility is already being monetized by everyone else. By headlines, by memes, by search traffic, by comment sections, by entire ecosystems built around looking at her. SYRN doesn’t create the gaze. It redirects it. It turns a cultural inevitability into a transaction she controls.

Justin Bieber is doing the same math from a different angle. His underwear and loungewear aren’t selling fantasy as much as access: softness, closeness, the suggestion of a private life made purchasable. Different vibe, identical leverage. Millie Bobby Brown built her hedge early. Brad Pitt reframed “serious actor” commerce into lifestyle credibility. Ryan Reynolds proved the modern version of stardom is ownership plus distribution plus a personality that performs on-command. These aren’t distractions from fame. They’re the new architecture of fame.

POPULAR ON THE CINEMA GROUP

That’s why the old critique feels outdated. The question isn’t whether celebrities should monetize. The internet has already made that decision. The question is whether they monetize passively through brands and platforms that extract value from their image, or actively through businesses that keep the upside in-house.

Hollywood used to treat commerce like a stain you had to hide. Now it’s just the balance sheet reality behind every “creative choice.” Acting is still the craft. But ownership is what buys time, autonomy, and the freedom to take creative risks when the algorithm stops being kind.

Underwear is not the weird turn. It’s the logical endpoint. Once you can sell someone what they wear under their clothes, you’re no longer borrowing their attention. You’re holding their trust.

And in a content-first economy, trust is the only currency that doesn’t crash overnight.