‘The Only Living Pickpocket in New York’ Review: John Turturro Gives a Career-Defining Turn in a City That’s Leaving Him Behind

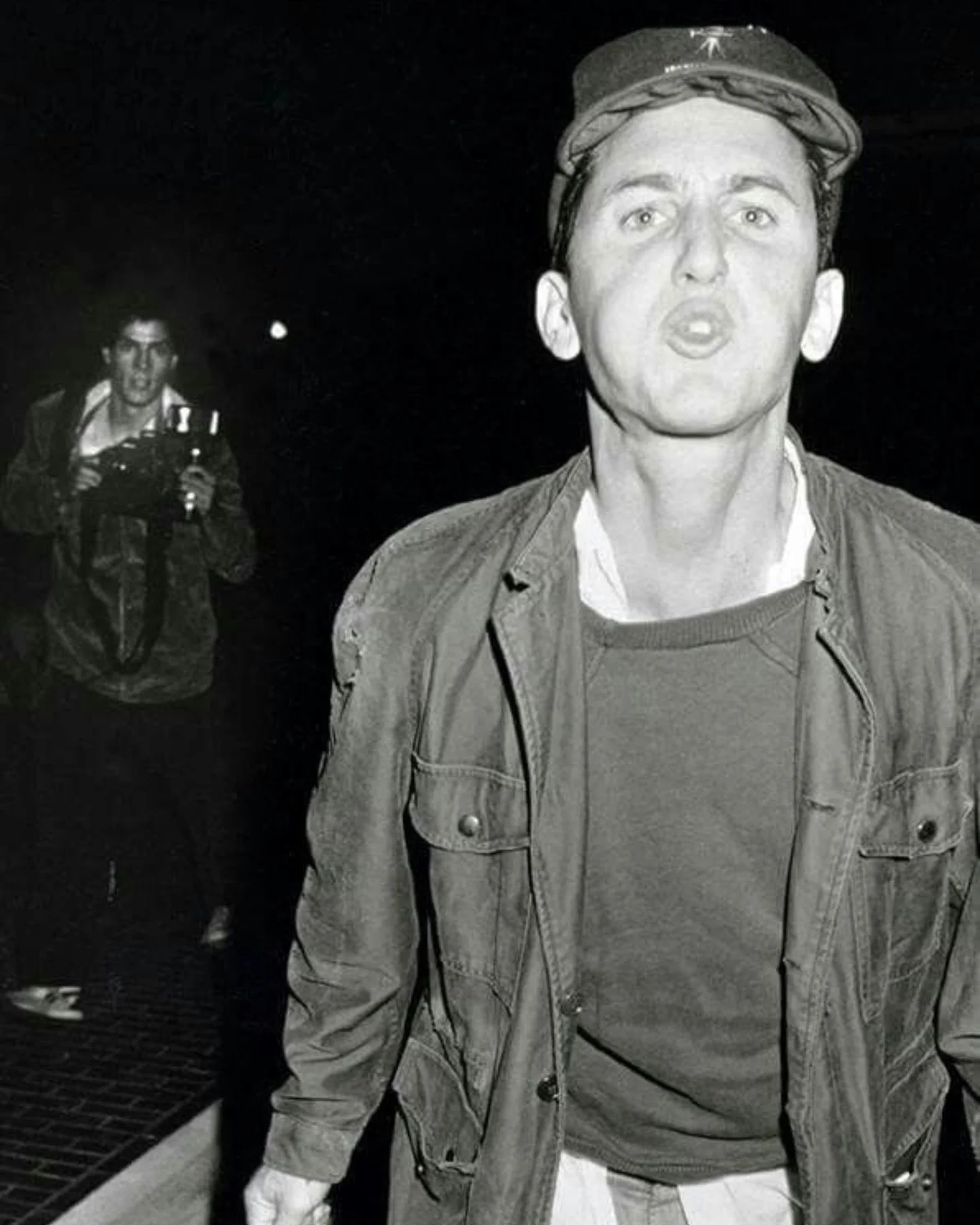

John Turturro in 'The Only Living Pickpocket in New York.' MRC II Distribution Company L.P./Courtesy of Sundance

John Turturro delivers one of the most quietly devastating performances of his career in Noah Segan’s intimate, street-level crime film about obsolescence, loyalty, and survival in a rapidly disappearing New York.

There are very few contemporary films that understand New York not as a backdrop, but as a living organism—one that remembers, resists, and slowly erases the people who once depended on it. The Only Living Pickpocket in New York, written and directed by Noah Segan, is one of those rare films. Modest in scale but deeply felt, it is a crime thriller that functions just as powerfully as a character study, a love letter, and a quiet elegy for a city—and a way of life—slipping out of reach.

At its center is John Turturro, giving a performance of remarkable restraint and emotional clarity as Harry Lehman, a career pickpocket who has survived not by ambition or violence, but by attentiveness. Harry doesn’t chase wealth or power. He watches. He observes rhythms, habits, vulnerabilities. He reads people the way the city once allowed you to—before cameras multiplied, before wallets disappeared into phones, before every corner felt surveilled.

Segan introduces Harry not through exposition, but through process. We watch him work—moving through subway cars, brushing shoulders, slipping away unnoticed. There is no bravado in these moments, no romanticized criminal swagger. Harry’s craft is quiet, almost meditative. It’s the work of someone who has spent a lifetime understanding how close you can stand to another person without being seen.

This is a film deeply invested in how people move through space. Harry walks with purpose but without urgency. He blends. He belongs. And yet from the beginning, there’s a sense that his belonging is conditional—that the city has begun to forget him.

Turturro plays Harry with a gentle melancholy that never tips into sentimentality. His face carries the weight of decades, but his eyes remain alert, curious, alive. There is dignity in the way he conducts himself, even as the world around him becomes less hospitable to someone like him. Harry is not a Robin Hood figure, but he operates by a personal moral code. He redistributes what he steals in small, human ways—helping neighbors, tipping service workers, quietly supporting the care of his wife Rosie, who lives with a disability that requires constant attention.

Rosie, played with tenderness by Karina Arroyave, is the emotional anchor of the film. Harry’s devotion to her is never framed as burden or obligation. It is simply love, expressed through routine: brushing her hair, lifting her up stairs when elevators fail, filling their apartment with old records and familiar melodies. These scenes are among the film’s most affecting, grounding Harry’s criminal life in something deeply human and quietly heroic.

Segan’s script excels at embedding character history into everyday behavior. We learn who Harry is not through speeches, but through repetition—through the way he returns to the same pawn shop, the same subway lines, the same routines that have kept him afloat. Steve Buscemi appears as Ben, Harry’s longtime fence and friend, a prickly but loyal presence who shares Harry’s nostalgia for an analog past. Their scenes together crackle with lived-in familiarity, underscored by the unspoken understanding that both men are nearing the end of their relevance.

The film’s central conflict arrives almost accidentally. Harry lifts a bag from a car belonging to Dylan, a volatile young criminal played with unnerving energy by Will Price. Inside the bag is not just a luxury watch or a gun, but something Harry doesn’t understand: a USB drive containing cryptocurrency. The object itself is almost abstract to him—proof that the economy he knows has been replaced by one he cannot see, touch, or fully comprehend.

This generational divide is one of the film’s most incisive themes. Harry is a man who works with his hands, his eyes, his instincts. Dylan belongs to a world of digital wealth, surveillance, and volatility. When Dylan realizes who took from him, the stakes escalate quickly—not through elaborate action set pieces, but through threats that feel disturbingly plausible. Harry is given hours to retrieve what he stole, under the explicit threat of violence against Rosie.

What follows is a tightly constructed race against time, but Segan never sacrifices character for momentum. Instead, the urgency sharpens the film’s emotional focus. Harry’s scramble to fix his mistake takes him across boroughs and into spaces that reflect the city’s layered social ecosystem—Chinatown storefronts, pawn shops, subway platforms, cramped apartments. Each location feels lived-in, specific, and essential.

Cinematographer Sam Levy captures New York with an unvarnished intimacy that recalls the city films of the 1970s, without slipping into imitation. The streets are crowded, imperfect, alive. There’s beauty here, but it’s the beauty of texture and friction, not polish. Levy’s camera observes rather than announces, allowing the city to reveal itself in glances, reflections, and passing moments.

One of the film’s most emotionally resonant sequences involves Harry’s estranged daughter Kelly, played by Tatiana Maslany with controlled intensity. Their reunion is brief but devastating—a collision of regret, anger, and unspoken longing. Maslany gives Kelly a hardness that feels earned, the result of years spent reconciling love with abandonment. The scene reframes Harry not as a romantic outlaw, but as a man who has failed in ways he cannot undo.

Giancarlo Esposito appears as Warren, a detective whose own career is being quietly sidelined in favor of younger, more tech-savvy officers. His scenes with Turturro are understated but loaded with mutual recognition. These are two men who understand that experience no longer carries the currency it once did.

Segan’s greatest strength as a director is his patience. He allows scenes to breathe, trusting silence and implication. The film’s climactic moments are not explosive, but cumulative—built on decisions that feel inevitable rather than convenient. Even the film’s surprise appearances and narrative turns are handled with restraint, serving character rather than spectacle.

The score by Gary Lionelli complements the film’s tonal balance beautifully, blending jazzy, retro textures with more somber, reflective passages as Harry’s options narrow. Music becomes another layer of memory, echoing the city’s past while underscoring the fragility of its present.

POPULAR ON THE CINEMA GROUP

At just under 90 minutes, The Only Living Pickpocket in New York feels remarkably complete. There is no excess here, no indulgence. Every scene serves a purpose, every relationship feeds into the film’s emotional architecture. The final act unfolds with a quiet inevitability that feels both painful and strangely comforting.

This is not a film about redemption in the conventional sense. Harry cannot undo his mistakes, reclaim his youth, or stop the city from changing. What he can do is choose how he exits—what he protects, what he leaves behind, and how honestly he faces the life he has lived.

John Turturro’s performance is extraordinary precisely because it refuses grandeur. He underplays every beat, allowing decades of experience to surface in the smallest gestures. It is a performance rooted in empathy rather than ego, and it lingers long after the film ends.

Noah Segan has made something rare: a crime film uninterested in mythology, a New York movie uninterested in nostalgia for its own sake, and a character study that honors the quiet resilience of people the city no longer sees.

Rating: ★★★★½

That's A Wrap

|

The Only Living Pickpocket in New York

|

That's A Wrap | The Only Living Pickpocket in New York |

“A beautifully observed, deeply humane crime film, The Only Living Pickpocket in New York cements John Turturro’s performance as one of the finest of his career while announcing Noah Segan as a filmmaker with uncommon emotional precision.”

CREDITS

Screened: January 26, 2026 | Sundance Film Festival

Cast: John Turturro, Giancarlo Esposito, Will Price, Tatiana Maslany, Steve Buscemi, Lori Tan Chinn, Kelvin Han Yee, Karina Arroyave, John Gallagher Jr.,

Victoria Moroles, Jack Mulhern, Michael Hsu Rosen, Aida Turturro, Mark Cayne

Writer-Director: Noah Segan

Out Now: Festival Circuit

Run-Time: 1 hour 28 minutes

Rating: R