‘Carousel’ Review: Chris Pine and Jenny Slate Find the Heart Beneath the Hesitation

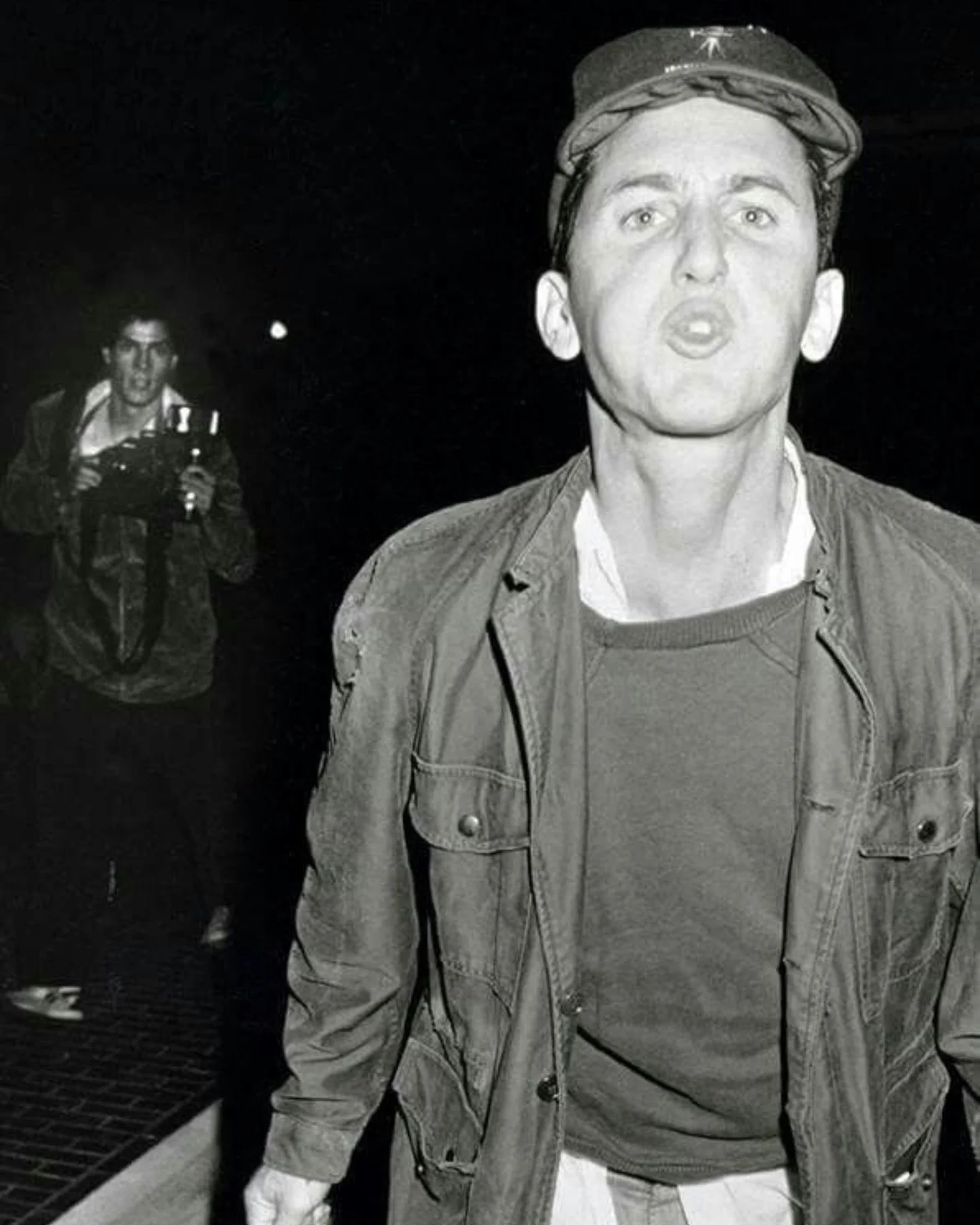

COURTESY OF SUNDANCE

Chris Pine and Jenny Slate turn a wobbly, over-scored start into a quietly devastating romance about the risks we avoid — and the love that still finds us anyway.

There’s something quietly maddening about how rarely Chris Pine and Jenny Slate are handed material this rich. They’re both actors who can make a single glance feel like a confession, who can shift from charm to damage in the span of a breath, and who have spent too much of their careers being used as flavor instead of the meal. Rachel Lambert’s ‘Carousel’ finally gives them a story with weight — the kind of intimate, adult drama that isn’t chasing a twist or a gimmick so much as it’s tracing the bruises people carry into their next chance at happiness.

And for a while, it almost gets in its own way.

Lambert opens the film with a heavy hand, leaning on an overbearing score that insists on telling you what to feel before you’ve had time to meet the characters. It’s not just present — it’s constant, crowding scenes that would be far more powerful if they were allowed to breathe. The musical motif is meant to echo the title’s metaphor: the looping, dizzying repetition of love, loneliness, and the patterns we can’t seem to escape. But it’s so aggressively signaled that it risks flattening the emotional complexity the film is trying to build.

Still, even in those early moments, Pine’s performance anchors the film with a lived-in exhaustion that feels instantly recognizable. He plays Noah, a Cleveland doctor running a small family medical practice, freshly divorced, emotionally worn down, and operating in survival mode. His entire life seems built around containment — keeping things steady, keeping the world from shaking too hard, keeping his teenage daughter Maya from slipping too far into her own anxiety.

Maya, played with aching precision by Abby Ryder Fortson, is the film’s early emotional pulse. Lambert sketches her depression and panic not as a plot device, but as a reality Noah has learned to tiptoe around. Their scenes together are the kind of domestic intimacy that doesn’t announce itself as “important,” which is exactly why it lands. Noah is attentive, patient, gentle — but also quietly avoidant, as if naming the problem out loud might make it permanent. That contradiction is one of the film’s smartest observations: love can be real, and still not be enough to fix what someone is carrying.

The film’s structure is intentionally oblique, sometimes frustratingly so. It withholds context, lets scenes drift, and asks you to sit in the discomfort of people who don’t quite know what they want — or who know exactly what they want and are terrified of it anyway. That hesitancy becomes the story’s defining tension once Rebecca enters the frame.

Slate plays Rebecca as Maya’s high school teacher and debate coach, a woman with a composed exterior that reads as brittle at first — not cold, but guarded. She’s someone who has built a life out of competence and distance, and Lambert is careful not to reduce her to a romantic ideal or a nostalgic “what if.” Rebecca is not the fantasy of a second chance. She’s the reality of one.

Noah and Rebecca reconnect almost by accident, crossing paths through Maya, and at first their chemistry is subtle — two people circling each other like they’re not sure they’re allowed to remember what they used to be. But Lambert slowly reveals their history: a relationship that ended in resentment when Rebecca left Cleveland to pursue a political career and Noah stayed behind to build a life that now feels like it’s collapsing in slow motion.

The film doesn’t rush them into romance. It lets the past sit between them like a third person in the room. The attraction is there, undeniable, but so is the damage. Pine plays Noah as a man whose sadness has become structural — not a temporary mood, but a way of moving through the world. He’s grieving his divorce, bracing for change at his clinic as his mentor prepares to retire, and carrying what feels like an unspoken wound related to his father. And even when love reappears in front of him, he treats it like something fragile he might break just by touching.

Then, midway through the film, ‘Carousel’ finally becomes what it’s been promising to be all along.

Lambert stages an extended confrontation between Noah and Rebecca in a kitchen, and it’s one of the year’s most quietly shattering two-handers — a scene that feels less like dialogue and more like two people bleeding out in real time. The choice to shoot much of it from the next room, partially removed, turns the moment into something voyeuristic and raw, as if the film itself is giving them privacy while still forcing us to witness it.

What makes the scene so devastating isn’t any single revelation. It’s the accumulation of emotional truths: anger that’s still alive, regret that never got resolved, tenderness that never fully died, and the exhaustion of realizing you’ve been protecting yourself for so long that you forgot what it feels like to be held. Pine and Slate cycle through defensiveness, longing, cruelty, humor, and surrender with an ease that feels almost indecent — like we shouldn’t be allowed to watch something this personal.

From that point on, Lambert’s restraint finally clicks into place. The score pulls back. The film stops trying to “announce” itself. The storytelling becomes more confident, more patient, and more emotionally direct. It’s as if the movie finally trusts its actors to do what they were cast to do: dig into the silence between the lines.

One of the smartest turns ‘Carousel’ makes is what happens when Maya leaves for a summer studies program at Stanford. The absence of Noah’s primary responsibility doesn’t free him — it breaks him. Without his daughter to manage, to protect, to monitor, he collapses into the version of himself he’s been holding at bay. There’s a sequence where he seems unable to even leave the airport, trapped in a kind of emotional paralysis, and Pine plays it with a specificity that makes it feel less like “a breakdown scene” and more like a man whose body has finally stopped cooperating with the lie that he’s fine.

Rebecca’s life is no less complicated. Lambert gives her a world outside Noah: aging parents, a friend nudging her toward a more ambitious path, the sense that she’s spent years building something that looks impressive but feels incomplete. Slate plays her yearning in small increments — a pause before she answers, a half-smile that disappears too quickly, the way her confidence cracks just enough to reveal how badly she wants to be chosen without having to beg for it.

What ‘Carousel’ understands — and what makes it quietly brutal — is that love is not the question. Love is the easy part. The hard part is whether you’re capable of accepting it when it arrives. Whether you can tolerate happiness without waiting for it to be taken away. Whether you can stop rehearsing your exit long enough to actually stay.

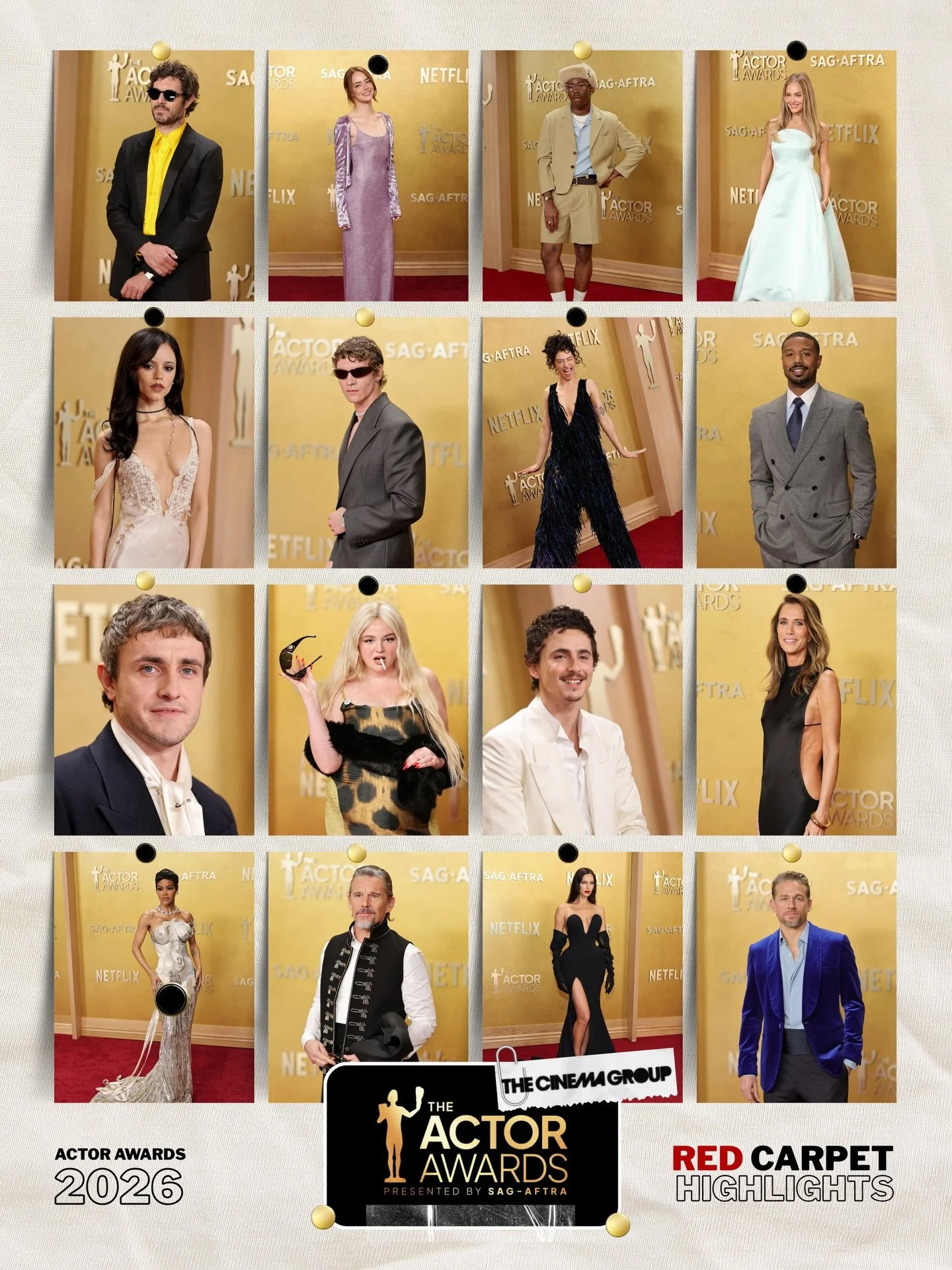

POPULAR ON THE CINEMA GROUP

Lambert’s direction is at its strongest when she leans into distance, framing key scenes as if we’re observing the characters from across a room, giving their intimacy a strange fragility. It’s melancholy without being hopeless, tender without being sentimental. The final scene, in particular, lands like a soft exhale — dimly lit, carefully composed, and full of the kind of hope that doesn’t feel like a guarantee, just a possibility.

Visually, cinematographer Dustin Lane shoots the film on 35mm in what appears to be an Academy ratio, bathing the story in soft light that makes everything feel enclosed and immediate. The look matches the emotional stakes: this is a film about small spaces — kitchens, clinics, classrooms — and the way a life can change in the quiet corners where no one is performing for an audience.

‘Carousel’ is not a perfect film. Its early stretch is overly mannered, and its score nearly smothers the intimacy it’s trying to create. But it’s also the kind of drama that sneaks up on you, slowly stripping away its own protective layers until you’re left with something painfully human. By the time it reaches its final movements, the film has earned its emotional impact — and Pine, Slate, and Fortson have delivered performances that remind you what real acting looks like when the writing finally gives them room to live.

In the end, ‘Carousel’ doesn’t spin in circles. It finds its center.

Rating: ★★★★☆

That’s a Wrap

|

Carousel

|

That’s a Wrap | Carousel |

“‘Carousel’ starts like a film trying too hard to be delicate — then it settles into something quietly devastating, carried by two performances that hit with the force of a memory you never outgrew.”

Credits

Airdate: Sunday, January 26 | Sundance Film Festival

Cast: Chris Pine, Jenny Slate, Abby Ryder Fortson, Sam Waterston, Katey Sagal

Creators: Rachel Lambert (Director/Writer)

Out Now: Premiering at Sundance 2026

Rating: Not Rated