On Swift Horses Review: A Queer Western Romance of Subversion, Longing, and the Ghosts of American Myth

'On Swift Horses' Sony Pictures Classics

Jacob Elordi and Daisy Edgar-Jones anchor a ravishing queer melodrama that reframes the Western as an elegy for unspoken lives and stolen dreams.

In a cinematic era characterized by franchise saturation, aesthetic homogeneity, and thematic conservatism, On Swift Horses emerges as a singular anomaly: a film that dares to imbue the romantic epic with a lush, queer sensibility, while also interrogating the ideological scaffolding of postwar American identity. Having attended an early screening in New York City, far from the film’s anticipated festival circuit premiere, I was struck not only by the audacity of Daniel Minahan’s vision but also by its palpable emotional architecture—every frame, every silence, every look is burdened with longing and possibility.

Adapted from Shannon Pufahi’s novel, the film unfolds in the early 1950s, a period saturated with mythologies of prosperity, domesticity, and heteronormativity. Against this cultural backdrop, On Swift Horses follows Muriel (Daisy Edgar-Jones), newly married to her returned-soldier husband Lee (Will Poulter), and her brother-in-law Julius (Jacob Elordi), a wounded drifter whose itinerant lifestyle masks a deeply internalized instability. Their lives become entangled in a slow-burning, emotionally elliptical narrative that examines the boundaries of desire, duty, and identity in a world not built to accommodate multiplicity.

From its very first moments, Minahan situates the film within dual iconographies: sex and games of chance. The juxtaposition of Muriel in an intimate moment with Lee and Julius arriving in Kansas with nothing but a deck of cards immediately signals the film’s preoccupation with bodily autonomy, probability, and the precarious nature of desire. These are not just narrative motifs but epistemological touchpoints—the lens through which the characters attempt to make sense of a world that often renders their internal landscapes illegible.

Muriel’s relationship with Julius is never defined by clarity or resolution but by emotional negative space. Their affection is mediated through letters, glances, and elliptical conversations that evade language. That their bond intensifies even as Muriel finds herself entangled with Sandra (a luminous Sasha Calle), and Julius initiates a volatile affair with Henry (Diego Calva) in Las Vegas, only deepens the film’s central inquiry: How does one ethically navigate multiplicity in a culture that demands singularity?

Minahan’s directorial style oscillates between painterly stillness and kinetic emotionality. The cinematography, characterized by wide-frame compositions that recall both Malick and Sirk, evokes the vastness of the American interior—not merely as a geographic space, but as an affective one. Each location, from the dusty highways of the Midwest to the shadowy velvet interiors of motel rooms, becomes a repository of longing and deferred possibility. The mise-en-scène itself seems to vibrate with secrets.

Jacob Elordi delivers a career-defining performance as Julius, abandoning the stoic braggadocio of his previous roles in favor of a vulnerable, melancholic masculinity rarely seen in contemporary cinema. He is by turns evasive and effusive, seductive and damaged—a cipher for the contradictions of a postwar American manhood that is both hegemonic and hollow. His scenes with Calva’s Henry are among the film’s most erotically and emotionally charged, but they resist the reductive arc of forbidden love; rather, they suggest that intimacy is most radical when it makes room for ambiguity.

Will Poulter and Daisy Edgar-Jones in 'On Swift Horses’ Sony Pictures Classics

Daisy Edgar-Jones, for her part, offers a masterclass in restrained emoting. As Muriel, she embodies the psychic dissonance of a woman both resisting and rehearsing domesticity. Her scenes with Calle’s Sandra, whose open queerness serves as a counterpoint to Muriel’s more coded subjectivity, provide some of the film’s most powerful moments—imbued with the tension of what might be possible if societal scripts were suspended.

Thematically, On Swift Horses positions itself as both homage and critique. It pays aesthetic tribute to the Western and melodrama traditions while deconstructing the ideological premises that undergird them. The West here is not a space of conquest but of disappearance, a terrain onto which the characters project their most desperate desires. Likewise, romance is not teleological but provisional; love is not salvation but strategy.

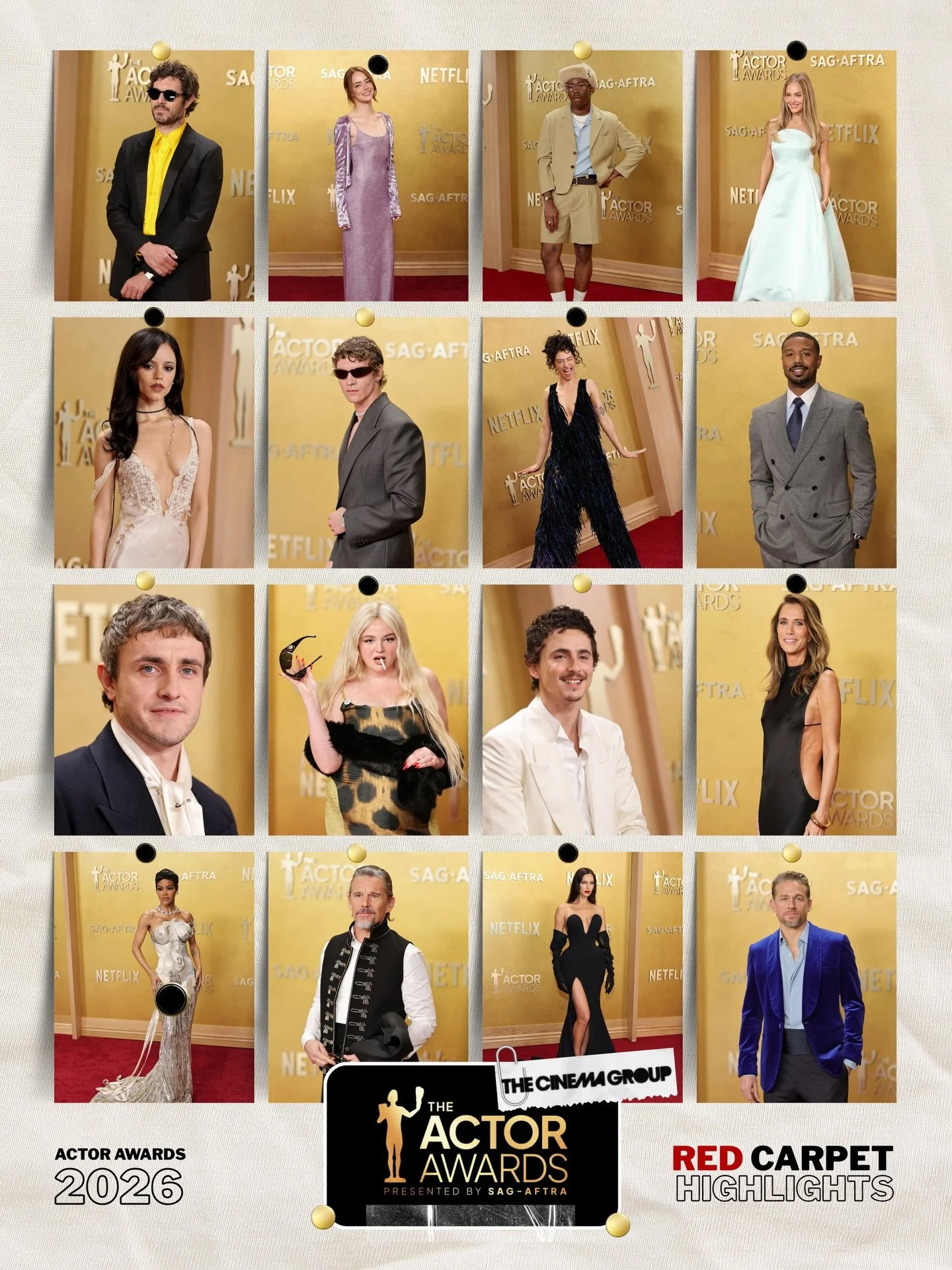

POPULAR ON THE CINEMA GROUP

If the narrative falters, it does so in its pacing. The film occasionally meanders, indulging in emotional digressions that, while visually sumptuous, detract from narrative cohesion. However, such indulgence feels consistent with the film’s larger aesthetic and philosophical commitments: this is not a story that wants to be tied up, but one that yearns to unravel.

Indeed, what On Swift Horses offers is not resolution but reverberation. It lingers—like a letter never sent, a caress withheld, a life unchosen. It is a cinematic text deeply attuned to the quiet violences of repression and the sublime dangers of authenticity. In a media landscape where queer narratives are too often relegated to subtext or tragedy, Minahan’s film insists on queer abundance—messy, contradictory, embodied.

This is cinema not merely as representation but as rupture, as re-imagination. It demands to be seen, to be discussed, to be rewatched. If this is what the revival of the romantic epic looks like—queer, expansive, intellectually rigorous—then let the renaissance begin.

A sensual, intellectually charged queer epic that dismantles the Western mythos from the inside out.

RATING: ★★★★☆

On Swift Horses

Cast: Daisy Edgar-Jones, Jacob Elordi, Will Poulter, Diego Calva, Sasha Calle, Don Swayze

Director: Daniel Minahan

Writer: Bryce Kass

Run Time: 1 hour 59 minutes