A House of Dynamite’ Isn’t Exploitation — Kathryn Bigelow’s Nuclear Thriller Is a Mirror.

Anthony Ramos as Major Daniel Gonzalez in A House of Dynamite. Cr. Eros Hoagland/Netflix © 2025.

Kathryn Bigelow’s latest film doesn’t manufacture fear. It measures it — showing us the thin line between security and delusion.

When Kathryn Bigelow’s A House of Dynamite premiered at the Venice Film Festival, it hit like a controlled detonation. Audiences emerged rattled, divided, and unable to shake its images — the eerie glow of radar screens, the sterile hum of war rooms, the haunting stillness of Rebecca Ferguson’s Captain Olivia Walker waiting for orders that might never come.

The early reactions were rhapsodic. Critics hailed it as “a masterclass in tension” and “Bigelow’s most politically urgent work since Zero Dark Thirty.” But as the film reached wider audiences this month, a countercurrent of skepticism emerged — some calling it alarmist, others dismissing its structure as implausible or overwrought. The debate mirrors the film itself: anxious, divided, searching for control.

It’s an old critique, often lobbed at artists who confront the unthinkable. But it misses the point entirely.

A House of Dynamite isn’t exploitation — it’s exposure. It’s not about nuclear panic, but about how our culture numbs itself to that panic. It’s a film that doesn’t exaggerate our fears; it diagnoses them.

Bigelow’s Cinema of Reality Distortion

(L-R) Anthony Ramos as Major Daniel Gonzalez and Abubakr Ali as Specialist Dan Buck in A House of Dynamite. Cr. Eros Hoagland/Netflix © 2025.

Kathryn Bigelow’s films have always operated at the intersection of adrenaline and analysis. She captures the high of intensity — then dismantles it. In The Hurt Locker, she weaponized suspense to examine addiction to danger. In Zero Dark Thirty, she built a moral maze out of methodical investigation. And now, in A House of Dynamite, she confronts the ultimate addiction: the illusion of control.

The film follows a 24-hour crisis within the U.S. government after a rogue nuclear missile is detected heading toward Chicago. We never learn exactly who launched it — or if it’s even real. The plot loops through three separate “episodes” of near-apocalypse, each one more disorienting than the last. Some Critique calling this “repetition”; Bigelow calls it reality.

The repetition isn’t narrative laziness — it’s psychological design. The more the characters react, the less they know. Each countdown exposes a new layer of miscommunication, misinformation, and institutional denial. The “enemy” becomes irrelevant. The real subject is our collective inability to process catastrophe.

In this way, A House of Dynamite doesn’t belong to the disaster genre at all. It’s a bureaucratic horror film — one where the terror is systemic, not cinematic.

Fear Is the Film’s Language — Not Its Product

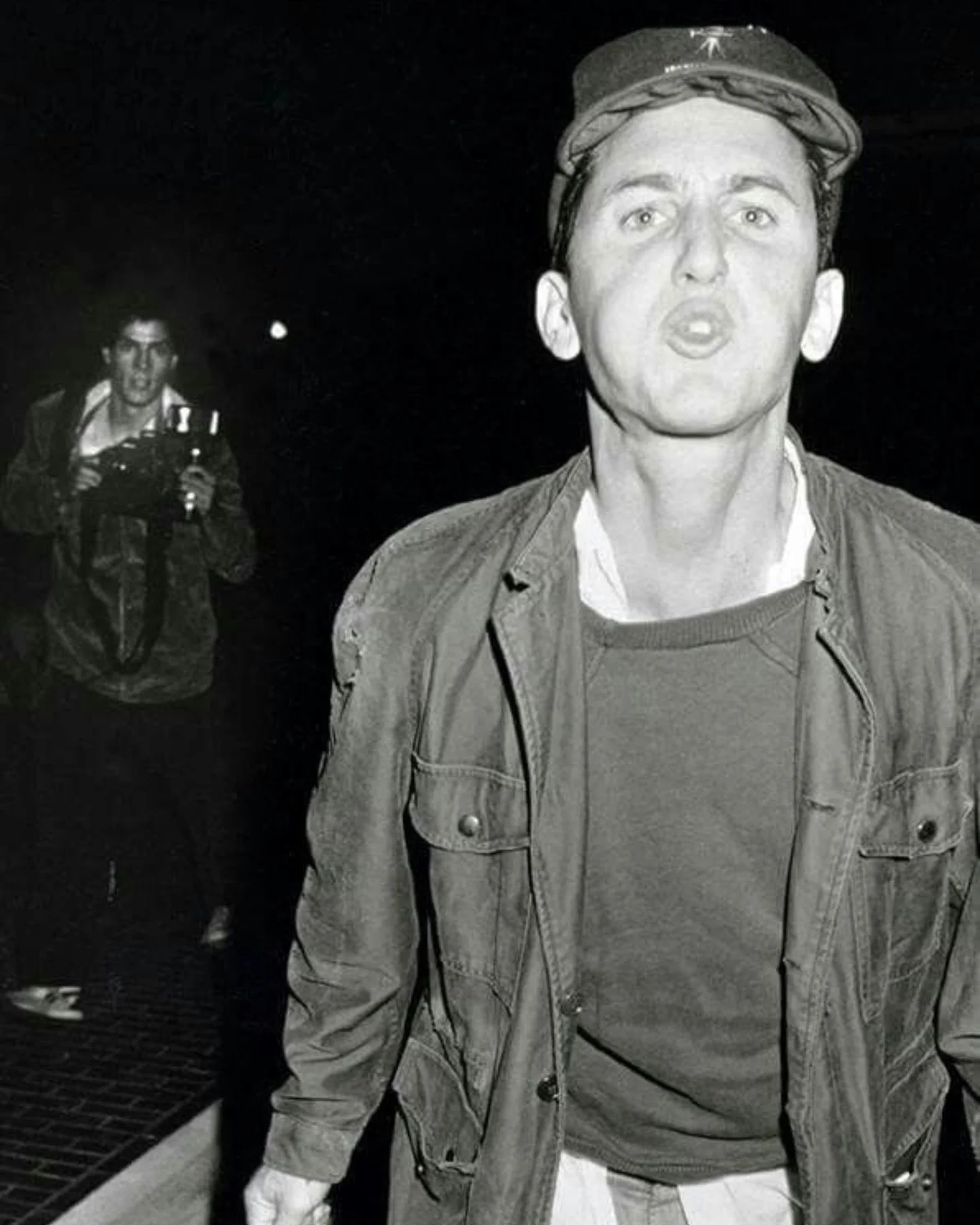

(Featured) Kyle Allen as Captain Jon Zimmer. Photo by Eros Hoagland. © 2025 Netflix, Inc.

To accuse Bigelow of “fear-mongering” is to misunderstand how she uses fear. In her hands, fear isn’t spectacle — it’s syntax. Some critics argue that A House of Dynamite “churns up anxiety” without evidence. But that anxiety is the evidence. It isn’t myth or science fiction. Whether the threat is imminent or distant, it exists — in us, in those who defend us, and in the systems we trust to keep us alive.

The true danger isn’t nuclear war itself; it’s our collective inability to comprehend one if it comes.

The film doesn’t lecture about warfare — it immerses us in the psychology of those living beneath its shadow. The unease we feel watching isn’t manipulation; it’s recognition. The tension mirrors the emotional fatigue of a world perpetually one miscalculation away from collapse.

When Jared Harris’s Secretary of Defense shouts, “So it’s a fucking coin toss? This is what $50 billion buys us?”, the line isn’t a throwaway critique of the military-industrial complex. It’s the moral center of the film — a metaphor for every institution that sells certainty in a world governed by chaos.

The subsequent metaphor — “a bullet hitting a bullet” — isn’t a contradiction; it’s the essence of modern defense strategy: faith masquerading as certainty. It’s the point. It’s the collision between probability and absurdity, between the cold precision of science and the inherent madness of trusting it absolutely.

A House of Dynamite is the rare thriller that doesn’t dramatize fear as something external. It exposes fear as the air we breathe.

The Cinematic Method Behind the Madness

Gabriel Basso as Deputy National Security Advisor Jake Baerington in A House of Dynamite. Cr. Eros Hoagland/Netflix © 2025.

Much of the criticism leveled at the film’s aesthetics — its handheld cinematography, its jittery pacing, its tonal coldness — echoes the same misunderstanding that met The Hurt Locker fifteen years ago. Bigelow’s visual style is often mistaken for chaos when it’s actually choreography.

Every shaky frame is anchored in geometry. Every close-up is calibrated to humanize the inhuman. The constant camera motion isn’t aesthetic indulgence; it’s kinesthetic empathy. It places the viewer inside an organism — the U.S. defense system — that’s brilliant, overactive, and profoundly flawed.

Barry Ackroyd’s cinematography, paired with Kirk Baxter’s editing rhythms and Volker Bertelmann’s minimalist score, gives the film its pulse. The tension is biological, not mechanical. When alarms blare and timelines collapse, we aren’t watching the end of the world — we’re feeling the erosion of understanding.

And Ferguson’s performance grounds it all. As Captain Walker, she’s the emotional and ethical axis of the film. Her stillness is not calm but compression — a soldier absorbing the panic her government refuses to acknowledge. When she whispers, “We’re not buying time, we’re borrowing it,” it lands like prophecy.

The Charge of “Exploitation” Misunderstands Bigelow’s Mission

Featured L-R) Tracy Letts as General Anthony Brady and Gbenga Akinnagbe as Major General Steven Kyle in A House of Dynamite. Cr. Eros Hoagland/Netflix © 2025.

Comparisons of A House of Dynamite to the disaster films of the 1970s like The Towering Inferno and Earthquake, accusing it of dressing spectacle as gravitas. But Bigelow’s entire career has been an argument against spectacle. Her violence is procedural, not operatic. Her explosions are internal.

If A House of Dynamite unsettles viewers, it’s because it dismantles the comfort of cinematic structure. It withholds catharsis. It denies resolution. That’s not exploitation — that’s ethics.

True exploitation relies on the audience’s powerlessness; Bigelow gives the audience responsibility. She forces viewers to confront their complicity in the very systems the film critiques: our appetite for stability, our faith in technology, our consumption of catastrophe as entertainment.

In doing so, she flips the cultural mirror. The exploitation isn’t in the movie — it’s in us.

The Political Cinema of 2025

Idris Elba as POTUS. Cr: Eros Hoagland © 2025 Netflix, Inc.

It’s no coincidence that A House of Dynamite arrives on Netflix in an election year marked by global unrest, AI militarization, and nuclear rearmament talks. The film’s release timing — and its polarized reception — speaks to a larger tension in our political storytelling: can art still provoke fear responsibly?

Bigelow’s answer is yes, but only if it provokes accountability too.

Her collaboration with screenwriter Noah Oppenheim, who draws from declassified data and military transcripts, gives the film its unsettling plausibility. They present not a prophecy but a simulation — a mirror of how modern defense operates: algorithmically, impulsively, chaotically human.

This realism has made some viewers uncomfortable precisely because it doesn’t flatter our confidence. A House of Dynamite challenges the myth of absolute control in a hyperconnected, nuclear-enabled world — the belief that someone, somewhere, “has it handled.”

The most chilling moment isn’t when the missile lands. It’s when the President (played with eerie restraint by Idris Elba) orders a retaliatory strike before confirmation — then retracts it when the data turns out false. It’s the ultimate Bigelow moment: a decision that saves the world but destroys certainty.

It’s no coincidence that A House of Dynamite arrives in a year defined by geopolitical volatility and existential unease. Nuclear rearmament, algorithmic warfare, and rising misinformation are not background noise — they’re the modern condition. Bigelow and screenwriter Noah Oppenheim turn that condition into moral architecture.

Fear as Reflection, Not Manipulation

(L-R) Anthony Ramos as Major Daniel Gonzalez and Abubakr Ali as Specialist Dan Buck in A House of Dynamite. Cr. Eros Hoagland/Netflix © 2025.

The public’s discomfort with A House of Dynamite mirrors the public’s discomfort with The Day After in 1983 — another film accused of “fear-mongering” that later influenced nuclear disarmament policy. To him, the movie’s dread feels manipulative because it isn’t cushioned by exposition or political reassurance. But that’s exactly what makes it necessary.

We live in a media landscape that aestheticizes fear to neutralize it. A House of Dynamite reclaims fear as something active — something that forces confrontation.

Its thesis isn’t “the world is ending.” It’s “the world might, and you wouldn’t believe how easily.” That’s not alarmism. That’s realism.

If the film feels like a punch in the gut, it’s because Bigelow is one of the few filmmakers still willing to swing at the American psyche. She’s not scaring us for sport. She’s waking us up.

The Cinema of Responsibility

A House of Dynamite. Cr. Eros Hoagland/Netflix © 2025.

There’s a moment near the end of A House of Dynamite when the crisis deescalates. The screen stays black for twelve seconds — no music, no dialogue. Just absence. Then the lights flicker back on, and the characters return to their desks, pretending nothing happened.

That moment is the entire film in miniature: a civilization so afraid of its fragility that it performs normalcy as survival.

POPULAR ON THE CINEMA GROUP

Bigelow isn’t exploiting fear; she’s exposing denial. Her film doesn’t scream that annihilation is imminent. It whispers that complacency already is.

So if you walk out shaken — good. You’re supposed to be. A House of Dynamite isn’t meant to soothe us into cinematic closure. It’s meant to hold the match close enough to see what we’re made of.

In a year where cinema has often felt toothless in the face of reality, Bigelow dares to remind us:

“the house isn’t just made of dynamite.

We’re the ones who built it.”

-Noah Oppenheim-

Bigelow’s film leaves us uneasy, that’s its triumph— because responsibility begins where comfort ends.

A House of Dynamite doesn’t exist to reassure us that the world is safe, but to remind us that safety is something we fabricate — a fragile performance we maintain to avoid seeing the truth. Bigelow’s brilliance lies in confronting that illusion head-on, forcing us to reckon with the systems we trust, the fears we bury, and the quiet complicity that lets danger thrive in plain sight.

It’s not a film about destruction; it’s a film about awakening — and the terrifying, necessary act of opening our eyes.